solar System

HOME

Mercury VenusEarth

Mars

Galerie Extra

|

|

|

Mercury

Mercury is the smallest and closest to the Sun of the eight planets in the Solar System, with an orbital period of about 88 Earth days. Seen from Earth, it appears to move around its orbit in about 116 days, which is much faster than any other planet. It has no known natural satellites. The planet is named after the Roman deity Mercury, the messenger to the gods.

Because it has almost no atmosphere to retain heat, Mercury's surface experiences the greatest temperature variation of all the planets, ranging from 100 K (-173 °C; -280 °F) at night to 700 K (427 °C; 800 °F) during the day at some equatorial regions. The poles are constantly below 180 K (-93 °C; -136 °F). Mercury's axis has the smallest tilt of any of the Solar System's planets (about 1/30 of a degree), but it has the largest orbital eccentricity. As such it does not experience seasons in the same way as most other planets such as Earth. At aphelion, Mercury is about 1.5 times as far from the Sun as it is at perihelion. Mercury's surface is heavily cratered and similar in appearance to the Moon, indicating that it has been geologically inactive for billions of years.

Mercury is gravitationally locked and rotates in a way that is unique in the Solar System. As seen relative to the fixed stars, it rotates on its axis exactly three times for every two revolutions it makes around the Sun. As seen from the Sun, in a frame of reference that rotates with the orbital motion, it appears to rotate only once every two Mercurian years. An observer on Mercury would therefore see only one day every two years.

Because Mercury moves in an orbit around the Sun that lies within Earth's orbit (as does Venus), it can appear in Earth's sky in the morning or the evening, but not in the middle of the night. Also, like Venus and the Moon, it displays a complete range of phases as it moves around its orbit relative to Earth. Although Mercury can appear as a bright object when viewed from Earth, its proximity to the Sun makes it more difficult to see than Venus. Two spacecraft have visited Mercury: Mariner 10 flew by in the 1970s and MESSENGER, launched in 2004, remains in orbit.

Internal structure

Mercury is one of four terrestrial planets in the Solar System, and is a rocky body like Earth. It is the smallest planet in the Solar System, with an equatorial radius of 2,439.7 kilometres (1,516.0 mi). Mercury is also smaller—albeit more massive—than the largest natural satellites in the Solar System, Ganymede and Titan. Mercury consists of approximately 70% metallic and 30% silicate material.Mercury's density is the second highest in the Solar System at 5.427 g/cm3, only slightly less than Earth's density of 5.515 g/cm3. If the effect of gravitational compression were to be factored out, the materials of which Mercury is made would be denser, with an uncompressed density of 5.3 g/cm3 versus Earth's 4.4 g/cm3.

Mercury's density can be used to infer details of its inner structure. Although Earth's high density results appreciably from gravitational compression, particularly at the core, Mercury is much smaller and its inner regions are not as compressed. Therefore, for it to have such a high density, its core must be large and rich in iron.

Geologists estimate that Mercury's core occupies about 42% of its volume; for Earth this proportion is 17%. Research published in 2007 suggests that Mercury has a molten core. Surrounding the core is a 500–700 km mantle consisting of silicates. Based on data from the Mariner 10 mission and Earth-based observation, Mercury's crust is believed to be 100–300 km thick. One distinctive feature of Mercury's surface is the presence of numerous narrow ridges, extending up to several hundred kilometers in length. It is believed that these were formed as Mercury's core and mantle cooled and contracted at a time when the crust had already solidified.

Mercury's core has a higher iron content than that of any other major planet in the Solar System, and several theories have been proposed to explain this. The most widely accepted theory is that Mercury originally had a metal-silicate ratio similar to common chondrite meteorites, thought to be typical of the Solar System's rocky matter, and a mass approximately 2.25 times its current mass. Early in the Solar System's history, Mercury may have been struck by a planetesimal of approximately 1/6 that mass and several thousand kilometers across. The impact would have stripped away much of the original crust and mantle, leaving the core behind as a relatively major component. A similar process, known as the giant impact hypothesis, has been proposed to explain the formation of the Moon.

Alternatively, Mercury may have formed from the solar nebula before the Sun's energy output had stabilized. It would initially have had twice its present mass, but as the protosun contracted, temperatures near Mercury could have been between 2,500 and 3,500 K and possibly even as high as 10,000 K.[24] Much of Mercury's surface rock could have been vaporized at such temperatures, forming an atmosphere of "rock vapor" that could have been carried away by the solar wind.

A third hypothesis proposes that the solar nebula caused drag on the particles from which Mercury was accreting, which meant that lighter particles were lost from the accreting material and not gathered by Mercury. Each hypothesis predicts a different surface composition, and two space missions, MESSENGER and BepiColombo, both will make observations to test them. MESSENGER has found higher-than-expected potassium and sulfur levels on the surface, suggesting that the giant impact hypothesis and vaporization of the crust and mantle did not occur because potassium and sulfur would have been driven off by the extreme heat of these events. The findings would seem to favor the third hypothesis; however, further analysis of the data is needed.

Surface geology

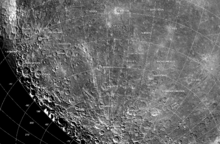

Mercury's surface is similar in appearance to that of the Moon, showing extensive mare-like plains and heavy cratering, indicating that it has been geologically inactive for billions of years. Because our knowledge of Mercury's geology has been based only on the 1975 Mariner flyby and terrestrial observations, it is the least understood of the terrestrial planets.[18] As data from the recent MESSENGER flyby is processed, this knowledge will increase. For example, an unusual crater with radiating troughs has been discovered that scientists called "the spider". It later received the name Apollodorus.

Albedo features are areas of markedly different reflectivity, as seen by telescopic observation. Mercury possesses dorsa (also called "wrinkle-ridges"), Moon-like highlands, montes (mountains), planitiae (plains), rupes (escarpments), and valles (valleys).

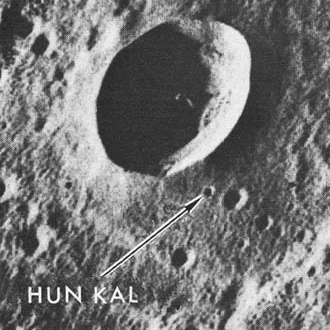

Names for features on Mercury come from a variety of sources. Names coming from people are limited to the deceased. Craters are named for artists, musicians, painters, and authors who have made outstanding or fundamental contributions to their field. Ridges, or dorsa, are named for scientists who have contributed to the study of Mercury. Depressions or fossae are named for works of architecture. Montes are named for the word "hot" in a variety of languages. Plains or planitiae are named for Mercury in various languages. Escarpments or rupes are named for ships of scientific expeditions. Valleys or valles are named for radio telescope facilities.

Mercury was heavily bombarded by comets and asteroids during and shortly following its formation 4.6 billion years ago, as well as during a possibly separate subsequent episode called the late heavy bombardment that came to an end 3.8 billion years ago. During this period of intense crater formation, the planet received impacts over its entire surface, facilitated by the lack of any atmosphere to slow impactors down. During this time the planet was volcanically active; basins such as the Caloris Basin were filled by magma, producing smooth plains similar to the maria found on the Moon.

Data from the October 2008 flyby of MESSENGER gave researchers a greater appreciation for the jumbled nature of Mercury's surface. Mercury's surface is more heterogeneous than either Mars's or the Moon's, both of which contain significant stretches of similar geology, such as maria and plateaus.

Impact basins and craters

Craters on Mercury range in diameter from small bowl-shaped cavities to multi-ringed impact basins hundreds of kilometers across. They appear in all states of degradation, from relatively fresh rayed craters to highly degraded crater remnants. Mercurian craters differ subtly from lunar craters in that the area blanketed by their ejecta is much smaller, a consequence of Mercury's stronger surface gravity. According to IAU rules, each new crater must be named after an artist that was famous for more than fifty years, and dead for more than three years, before the date the crater is named.

The largest known crater is Caloris Basin, with a diameter of 1,550 km. The impact that created the Caloris Basin was so powerful that it caused lava eruptions and left a concentric ring over 2 km tall surrounding the impact crater. At the antipode of the Caloris Basin is a large region of unusual, hilly terrain known as the "Weird Terrain". One hypothesis for its origin is that shock waves generated during the Caloris impact traveled around the planet, converging at the basin's antipode (180 degrees away). The resulting high stresses fractured the surface. Alternatively, it has been suggested that this terrain formed as a result of the convergence of ejecta at this basin's antipode.

Overall, about 15 impact basins have been identified on the imaged part of Mercury. A notable basin is the 400 km wide, multi-ring Tolstoj Basin that has an ejecta blanket extending up to 500 km from its rim and a floor that has been filled by smooth plains materials. Beethoven Basin has a similar-sized ejecta blanket and a 625 km diameter rim. Like the Moon, the surface of Mercury has likely incurred the effects of space weathering processes, including Solar wind and micrometeorite impacts.

Plains

There are two geologically distinct plains regions on Mercury. Gently rolling, hilly plains in the regions between craters are Mercury's oldest visible surfaces,[39] predating the heavily cratered terrain. These inter-crater plains appear to have obliterated many earlier craters, and show a general paucity of smaller craters below about 30 km in diameter. It is not clear whether they are of volcanic or impact origin. The inter-crater plains are distributed roughly uniformly over the entire surface of the planet.

Smooth plains are widespread flat areas that fill depressions of various sizes and bear a strong resemblance to the lunar maria. Notably, they fill a wide ring surrounding the Caloris Basin. Unlike lunar maria, the smooth plains of Mercury have the same albedo as the older inter-crater plains. Despite a lack of unequivocally volcanic characteristics, the localisation and rounded, lobate shape of these plains strongly support volcanic origins.All the Mercurian smooth plains formed significantly later than the Caloris basin, as evidenced by appreciably smaller crater densities than on the Caloris ejecta blanket. The floor of the Caloris Basin is filled by a geologically distinct flat plain, broken up by ridges and fractures in a roughly polygonal pattern. It is not clear whether they are volcanic lavas induced by the impact, or a large sheet of impact melt.

One unusual feature of the planet's surface is the numerous compression folds, or rupes, that crisscross the plains. As the planet's interior cooled, it may have contracted and its surface began to deform, creating these features. The folds can be seen on top of other features, such as craters and smoother plains, indicating that the folds are more recent. Mercury's surface is flexed by significant tidal bulges raised by the Sun—the Sun's tides on Mercury are about 17 times stronger than the Moon's on Earth.

| up | Links: Google.en. Wikipedia.org | |